by RUSSELL THOMPSON, Apples and Snakes

I entered archiving through a back door: I was someone who knew a lot about spoken word (or thought I did), but little about the true nature of being an archivist. Maybe that was a help, maybe it wasn’t. I’m still not a qualified archivist, but there are a number of things I know now that I wish I’d known when I embarked on the first iteration of the Spoken Word Archive (SWA) project.

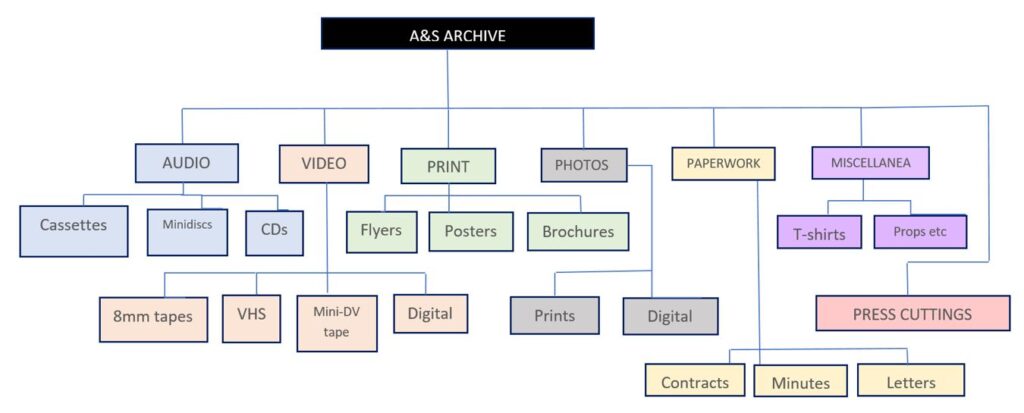

Spoken Word Archive was an attempt to make sense of the history of Apples and Snakes (A&S), the organisation I’d then worked for for nearly a decade, but whose history already stretched back for more than 30 years. A&S was, and is, a London-based literature development organisation specialising in the promotion and development of spoken-word poetry through education and live performance. Its archive consisted, at that point, of a walk-in cupboard full of paperwork, tapes and photos in varying states of orderliness. These items told the story of a volunteer-run cabaret night that had grown into a professional organisation with five offices around the UK. A colleague had made a fair degree of headway cataloguing the boxes of promotional flyers and posters in the early years of the millennium, but other than that, little had been achieved.

My brief was therefore to digitise everything and to finish cataloguing it. The assets were then to be presented to the world on a purpose-built website. The first two-year part of the initiative was financed by the Heritage Lottery Fund, and seemed to take place at a time when several performing arts organisations were having similar thoughts about preserving their history. One clause in the funding agreement, however, stipulated that the project should not simply record the activities of a single organisation – it had to have a wider application. Although various people advised me not to take this too literally, my colleagues felt that we should cover ourselves by using an umbrella-like title – Spoken Word Archive – which would leave the door open for the website to be used as a hub for the archives of other spoken-word organisations once work on A&S’s had been completed. Whether this is still a desirable or a realistic outcome remains debatable.

I set this project in motion with the intention that I would coordinate it – although because the funding was to cover the coordinator’s salary, this necessitated going through an interview process. Luckily things went in my favour on the day – after which I was left facing the day-to-day practicalities of how to get the job done. For a start, I would be entirely reliant on voluntary assistance: our application had pledged that the project would engage a certain number of volunteers. This meant that each volunteer would work with us for a limited time – the downside of which was having to say goodbye to some hardworking and dedicated assistants just at the point when they seemed to be hitting their stride. There were other volunteers who would turn up for perhaps two weeks and then never return, having presumably realised that archiving was perhaps not quite what they’d expected (there are a lot of spreadsheets involved!).

Like I say, archiving was as new to me as it was to most of the volunteers. My chief advantage was that I had been steeped in A&S for the previous eleven years, in the role of London Programme Coordinator (or equivalent – the job title was prone to rebranding) and consequently understood the nuances of piecing together aesthetically pleasing events whilst staying within the twin orbits of marketability and organisational strategy. In a sense, I was also someone who had grown up alongside the genre, from falling in love with Joolz Denby and John Hegley via late-night radio broadcasts whilst I was still at school, to being a practitioner of the artform myself and understanding that it was as much about long train journeys and sleeping on sofas as about the ‘glamour’ of being on stage. Joking apart, I was always very aware of being part of the development and dissemination of an underground genre that seemed constantly poised to erupt into the mainstream (my performing career was taking off, in a modest way, in the first half-decade of the new millennium, shortly before Kae Tempest arrived on the scene and shifted the aspirations of spoken-word artists to a much more rarefied level) and I was fascinated by the notion of where the whole thing had actually originated.

Of course, I needed a framework. I had always visualised A&S’s assets being archived on an event-by-event basis – each event being a live performance that had taken place. Each event-page would then be cross-referenced with links to pages about each of the poets involved and the venue where the show occurred. The most daunting aspect of this plan was the sheer scale: even in 2015, there had been approximately 2,500 A&S shows and a similar number of poets. Already that amounted to a lot of pages.

The company we engaged to design this website specialised in heritage projects, although their work tended to focus on communities in the geographic sense. As I saw it, our archive was essentially the same, but the community was an artform. I did get the impression, however, that the designers always regarded the physical archive – the assets themselves – as the backbone of their projects, and that it was unusual for something as intangible as ‘events’ to fulfil that role.

Either way, I had to get cataloguing, which was a voyage of discovery in itself. The website builders had discussed this process with me at some length. If you’ve got a collection, everything has to have a catalogue number, which is fair enough. For some time, though, I laboured under the misapprehension that these numbers had to ‘mean’ something. I didn’t really understand that you could just pluck them out of thin air. But if you look at my numbers, you’ll see that they still bear fossilised traces of those earlier assumptions: the cassette designated C989001, for example, started out as C1989/001, chronologically the first tape from 1989. In the end, I just docked off the first digit and the oblique stroke to make the number shorter. For items whose date was uncertain, I used the year 1381, the year of the Peasants’ Revolt, which I thought chimed nicely with the original ideals of A&S. Hence all those tapes beginning C381…

The most important aspect of any website is that it serves its correct purpose for the correct people. Searchability is key for any researcher, and unfortunately this has never been the strongest suit of the SWA site: it has not been unknown for its search function to seize up and remain inactive for a period of time, despite the builders’ assurances that there is nothing wrong with it. Also far from ideal is the builders’ preference for alphabetising the poets by their first name rather than their surname, but it was explained to me early on that the latter would be difficult to implement. As someone who uses libraries and enjoys books with proper indexes, I still find this system counter-intuitive. But never mind.

As for the question of who is using the site, the indication is that they are largely people researching one particular artist and are interested in whatever archival material we may possess – not all of which is yet available on the site. We have received enquiries about Jayne Cortez, Leonora Rogers-Wright, Lydia Tomkiw and Lioness Chant, amongst others. The Cortez contact was curating an exhibition in New York, so it was nice to know that the archive was being used internationally.

Of course, one danger of concentrating on the archival records of a single organisation is that its activities are shaped by the predilections of a small quorum of people or, indeed, of just one person. These may be a product of programming policy or taste, or both. A swift glance at the website soon reveals that, for half a decade, the flagship of A&S’s programming was its annual Jazz-Poetry Festival. And yet that shouldn’t be taken as a sign that jazz-poetry fusion was a major feature in UK spoken word in the years immediately straddling 1990. Look at flyers from other poetry-cabaret events from the same era – the ones Nick Toczek was running in Bradford, for example – and you’ll see a different stylistic bias. And indeed, when there was a change of personnel at A&S, the jazz-poetry bonanzas came to an abrupt halt.

Human agency is just as much a feature of the archiving as of programming. Early on, someone told me that it’s equally about what you choose to leave out as what you leave in. The key word here is ‘choose’, because it’s a curatorial role. Archiving is dangerous for people who are easily distracted and are inclined to go down rabbit-holes, gripped by the idea that, well, it all adds to their understanding of cultural and historical context. It’s like chaos theory in that every rabbit-hole has a whole warren leading off it. Every show, every artist, every venue is a story waiting to be told, and all of us are attracted by obscurity. For instance, I’d always been intrigued by one of the names on the flyer for the very first A&S show, Outbar Squeek. Was it a person? Was it an ensemble? It turned out to have been a band – one of many that peppered the bills in the early days, ostensibly to pacify audiences who might struggle with the idea of an entirely poetry-orientated night – and I was ridiculously pleased when I finally tracked them down. Their frontman sent me a 20-page biography of the act, which I posted on the SWA website. In the meantime, another 2,499 performers were going unresearched.

To describe archiving as ‘curatorial’ is perhaps an oversimplification, however, because curation usually comes with an angle, a prism through which to view things. One could tell A&S’s story from a feminist point of view, an LGBT point of view, and countless other standpoints. It gradually occurred to me that my role was to simply present the materials in an impartial manner, and leave the interpretation to others.

What was really unexpected was the vastness of the undertaking. My advice to anyone embarking on a similar project, from a comparable point of relative inexperience, would be to calculate an anticipated timeframe for the work and then multiply it by about five. This allows for all the cul-de-sacs and unforeseen accidents. (I speak from bitter experience here: a hard drive containing two months’ work by a particularly efficient volunteer fell off the high shelf where I’d foolishly stored it, and broke. Even more foolishly, I’d not backed it up – and the damage turned out to be too severe for the material to be salvageable). The digitisation of analogue recordings, of course, can only be done in real time: a 90-minute tape takes 90 minutes to digitise. More, in fact, because extra time is required to set the levels and format the files. Very naively, our initial plan was to do all the digitisation in-house, since we figured that we needed to have something for our volunteers to actually do. The impracticability of this soon became evident, and extra funding had to be sought so that the work could be farmed out to a third party. Luckily the third party had an office in the same building as us and had a known track record, so this move came with the double assurance of knowing that the materials wouldn’t be lost in transit and that the work would be done well.

On the subject of the recordings, we were lucky in that the tapes had been stored in fairly good conditions, and that most of them had presumably never been played since the night they were recorded. Ferric tape can deteriorate, as we know. And things go missing. At some point, for instance, we must have had recordings of the shows we ran in the latter half of 1990s – but we don’t know where those are. Lost in an office move? That’s a lot of tapes to just ‘lose’. A few years ago, one of the previous directors of A&S arrived in the office with two heavy-duty supermarket bags full of tapes that she’d found in her house – not the ones mentioned above, but it was a heartening reminder that things can sometimes still come to light. More galling, perhaps, was the tale I heard from the same ex-director about the temp who came in as maternity cover and ‘tidied up’ the filing cabinet by binning all the old bits of paper it contained. This is why a lot of flyers covering a certain period in the early 1990s are missing.

As well as learning about archiving, I discovered a lot about how an artform develops. Laying out everything chronologically, you get a sense of how genres mutate, split into sub-genres or vanish altogether. For instance, several of the late 1980s and early 1990s flyers mentioned choreopoetry, a term coined by the American poet Ntozake Shange to describe a stage show combining elements of poetry, music, theatre and dance – the opposite of the great tradition of ‘read off the page and just busk it’. It’s arguable that British tours by various US choreopoets – Shange herself in 1988, Will Power in 2001 and 2003 – acted as catalysts for the UK’s own spoken-word theatre scene. Certainly homegrown shows from that era such as Roger Robinson’s Shadow Boxer seem to represent a major leap forward in terms of thinking about staging and presentation.

It’s also interesting to consider the inroads that rap and hip-hop have made into British spoken word. It sometimes feels as though the influence is all-pervasive, in the way that certain rhythms and the use of assonance, for example, have been adopted by artists who may seem, on the surface, to have very little connection with that genre. And yet, if you look at the A&S listings, at least, those influences took a long time to properly take hold: there’s the best part of a decade between the September 1979 release of ‘Rapper’s Delight’ – the record that took hip-hop off the streets and into the living rooms – and the word ‘rap’ cropping up regularly in A&S’s publicity. For the majority of the 1980s, dub poetry and rapso (its Trinbagonian equivalent, based around soca rhythms) were much more prevalent. It’s true that cultural shifts happened at a slower pace in pre-internet days, but even so, it’s a surprise to see just how long one stylistic shift could take.

Archives are ultimately about people, and my work on this one has been a telling reminder that they, like tapes and flyers, are ephemeral. Early on in the process, the A&S archive team and I filmed talking-head interviews with a few major players from the scene. Of these, Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze and Benjamin Zephaniah are no longer with us – both of them dying far too young. I also carried out audio interviews with the organisation’s founders, and one of these, the anarchic performer Emile Sercombe, has now also passed away. Other significant characters, such as Michael Horovitz, died before I had a chance to speak to them at all.

Apples and Snakes Interview with Benjamin Zephaniah

This underlines why the last few years have been the right time to pull this archive together. Events lose some of their tangibility when they pass out of living memory. Simultaneously, the history of performance poetry has passed a watershed moment: it was only a few years ago that people realised that it had a history. This was why we initiated our project in the first place: it gradually dawned on us that we were sitting on an archival goldmine. Since then, things have truly opened up, with books such as Pete Bearder’s Stage Invasion and the Routledge compendium Spoken Word in the UK offering approaches to the study of the topic in the British context.

My last two and a half years’ work on Spoken Word Archive has been supported by the European Research Council as the Liaison Archivist for the Poetry Off The Page team. In this capacity, I have been tasked with assisting the members of the team with their individual lines of research – sometimes remotely, sometimes in person. My approach to the archive has benefitted greatly from seeing the extent to which the team have found it user-friendly and sufficiently geared-up to their areas of interest. I am very grateful to Dr Julia Lajta-Novak and the rest of the team for giving me this opportunity. The moot point is whether an archive can ever truly be complete. For an active arts body like Apples and Snakes, the event that happened last night is now archival. The organisation’s prime focus, quite rightly, is what’s coming up on the horizon – next week, next month, next year. But there’s always that little voice in the corner of the office saying, ‘Yes, but remember what happened in 1987’ – and for the last few years, that’s been me.

***

RUSSELL THOMPSON is the liaison archivist for Poetry Off the Page. He spent a decade as London programmer for Apples and Snakes, followed by two years coordinating their archive project and helping to build the archive website. As a practitioner of the artform himself – performing as Rachel Pantechnicon and one half of Project Adorno – he has taken a dozen shows to the Edinburgh Fringe, and his CV includes appearances at Glastonbury, WOMAD, and Latitude. He juggles his PoP work with a complementary (and equally fascinating) job at the National Poetry Library in London.

***

To cite this blog post:

Thompson, Russell. “2,500 Poets and Counting: My Life as a Spoken-Word Archivist.” Poetry Off the Page, 02 May 2024, https://poetryoffthepage.net/2500-poets-and-counting-my-life-as-a-spoken-word-archivist/.

Header image © SpokenWordArchive.org / Apples and Snakes.

All other images: © Russell Thompson.

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.