by FRANZISKA KLEIN

Navigating queer spoken word poetry with the potential expectations placed on queer performers by both heteronormative and non-heteronormative society can prove a challenge. As spoken word poetry continues to grow both through offline events and online platforms such as YouTube, queer spoken word poetry, poetry performed by queer poets and/or covering queer topics continues to grow with it. Yet, there is very little academic literature on queer spoken word performance and its analysis. This blog entry aims to provide a way of including queer spoken word poetry into academic discourse, bringing together studies on queer poetry and embodiment to shed light on spoken word poetry. I will focus on three concepts of queer theory and apply them to spoken word performance: queer spoken word and the death drive; the performativity and embodiment of spoken word performances; and queer life writing of pasts and futures.

As a case study, I will focus on Ethan Smith’s “A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be” performed 15 March 2014 at the College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational Final in Boulder, Colorado. Following the Slam Final, Button Poetry, the US spoken word company and event organizer, shared a video of Smith’s performance via its YouTube channel and gained an audience of over 1.5 million viewers and over 1,000 comments. In his poem, Ethan Smith speaks to his identity as a transgender man by performing a letter to ‘Emily’, presumably the female identity he was known as before coming out as trans. He takes the audience through his experience of growing up, including therapy sessions and suicidal thoughts, the changes his body went through during transition, and the sacrifices he made to become the man he is today.

Queer Spoken Word and the Death Drive

Queer identity has been identified within critical and cultural theory as posing challenges to and transforming definitions of death, and of what it means to be – and stay – alive. For any individual, ‘the body’ forms part of the essential experience of being alive, and it is simultaneously regulated by social and cultural norms to fulfil normative conditions of ‘liveness’, a term used by Mel Chen in Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (2012). Such established expectations and regulations imposed on the body, or ‘fictions’ as Mel Chen suggests, include integrity, autonomy, and heterosexuality (Chen 8). This compulsory heterosexuality is linked to reproductive futurism, the “belief that our participation in politics [and normative society] is motivated by a belief in and a desire for creating better futures for our children” (Poutinen par. 2; cf. Edelman 2) which will, in turn, keep society alive.

Queerness, both in terms of bodies as well as sexuality, challenges these understandings of liveness. Queer bodies call into question the fictions imposed by heteronormative assumptions about gender identities. For example, non-binary bodies break free of the binary gender system, and transgender people transition to the gender they identify with. By dismantling the fiction of how a body must look to be alive, queer bodies show that there are many more ways to fulfill this liveness. Similarly, queerness confronts normative ideas of heterosexuality. According to Edelman’s concept of reproductive futurism, the political and societal purpose of heterosexuality is to reproduce in order to preserve and maintain the existence of human society. This reproductive goal defines reproduction as the only normative means of securing society’s future. Queerness contributes to what Edelman calls the ‘death of society’, meaning the death of society as a system that equates children with the future, because queer sexuality is not inherently based on reproduction (29). By resisting compulsory heterosexuality, queer people and queer relationships highlight the possibilities of alternative modes of being, a counter discourses. Queerness complicates the singular heteronormative idea of society and creates new ways of living and identifies possible futures independent of reproduction. Queer spoken word performance, I contend, has the potential to highlight these discrepancies.

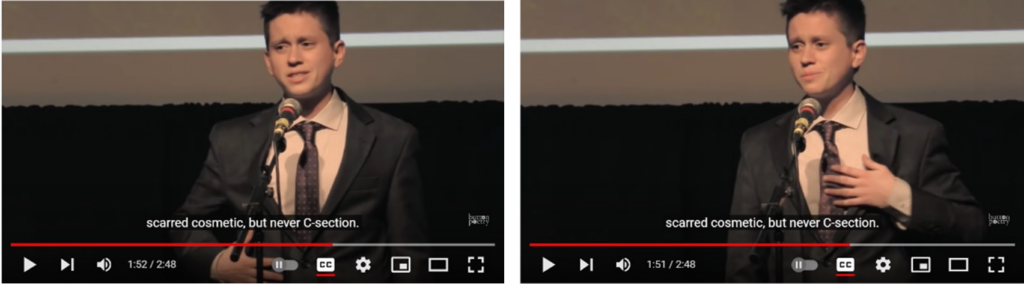

In Ethan Smith’s performance of “A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be,” the challenges that both queer bodies as well as queer sexualities invite on normative society’s definition of liveness are performed for an audience. In his autobiographical performance, Smith presents a letter to his past self, recalling how his body changed during his transition from female to male (Strudwick n.p.). He states: “My body is obsolete, scarred cosmetic, but never C-section.” While performing this phrase, he gestures first to his chest in reference to a double mastectomy as part of his transitional story (see Fig. 1). This gesture clearly references the scars left by surgery on his upper body. Following this, he underlines the statement “but never C-Section” with a gesture across his abdomen, where the scar of a C-section would be (see Fig. 1). These gestures play a significant part in the ways in which spoken word poetry can highlight the presence of the queer body, as they convey information that is not present within the written form of the text and are unique to Smith’s performance.

By juxtaposing the scars of his transition with those that might (or should, according to the reproductive pressures of society) have been left upon a woman’s body via the act of giving birth, Smith highlights how queer and trans bodies construct their own notion of autonomy and aliveness. Rather than adhering to what heteronormative assumptions dictate a body to be in order to count as ‘alive,’ trans people follow their own queer definitions of what their body must look like in order for them to be alive as the person they feel themselves to be.

Smith also links the scars from his mastectomy with another part of his transitional journey by recounting the effects of testosterone on his body’s potential to conceive children. He expresses the hormones’ sudden impact on his menstrual bleeding by using repetitions: “I was four days late … I was one week late … I was eleven days late … I was two weeks late … I was three weeks late … I was two months late.” This phrasing reinforces the connection to reproduction, as ‘being late’ is a term commonly associated with the cessation of periods following pregnancy. Additionally, Smith uses his hands to count out the numbers used in the poem and speeds up while recounting the timeline of this interruption of his menstrual cycle (see Fig. 2). These bodily and voice measures, uniquely available to spoken word poetry performance, powerfully convey the rapid and significant changes Smith’s body underwent.

The lines “I thought about your [Emily’s] children, how I wanted them too” suggest that the ability to conceive his own children represents an important topic for Smith. He continues to address this loss of never being able to give birth to children in the phrase, “They will never shout ‘watch mommy, watch me on the slide’,” echoing reproductive futurism’s ideal of the child as central point of life. Smith’s performance gestures towards grief as he describes the ways in which his body has become ‘obsolete’, unable to generate or ‘nourish’ new life (01:37-02:08). However, the poet’s embodied presence on stage, which is a significant element in spoken word performance, shows that Smith has voluntarily chosen to prioritise the existence of his queer body over normative ideals of reproduction.

Moreover, Smith speaks directly of death as a counterpoint to his liveness by addressing his performance to Emily, the name he was given before his transition and unknown to his friends until this performance (01:12). In the LGBTQ+ community, this is conventionally known as a ‘dead name’. This term marks an explicit distinction between the ‘death’ of a person conforming to cisgender norms, and the living trans person. Smith remembers that “in therapy you [Emily] said you wouldn’t make it to 21… and you were right” (00:50-00:57) as his personal poetic narrative declares his past self as dead, and his present self as alive and performing.

Representation and Queer Embodiment

In the same way that Smith’s embodied presence adds a layer to the discourse around reproduction and futurity, his clothing challenges and adheres to standards of masculinity. Aside from a poet’s words and gestures, artifacts such as objects, clothing, and cosmetics can have an impact on a live performance of poetry (Fine qtd. in Novak 168). A performer’s specific clothing choices, for example, can help them create a specific persona on stage, or ‘identify him/her as (not) belonging to a specific group’ (Novak 169). In addition, Katie Ailes argues that in spoken word, there is an implicit expectation that poems present honest and real representations of a performer’s desires and life experiences. The “performer’s body serves as an authenticating factor,” (145) meaning that the body on stage can strengthen the conflation between the lyrical ‘I’ and the performer in the same way that clothing choices help to reinforce this connection for the audience.

Smith’s clothing choices for the performance of “A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be” simultaneously reinforce queer and normative masculinity. He wears a pair of black jeans, a black suit jacket, combined with a white shirt and a purple tie and does not wear any visible make-up or jewelry. As a consequence, his clothing creates a traditionally masculine image, highlighting his transitional journey as a trans man. Preconceived notions of masculine presentation (i.e. the suit) therefore mark him as being a member of a specific group of men. For the audience, this reinforces an autobiographical journey away from Emily, who is present in the poem, and towards Ethan, who is present on stage. By playing into society’s normative standards of clothing as a marker for his masculinity, Smith reinforces such standards. However, by publicly declaring his identity as a trans man through the performance of his poem, he presents a clear challenge to normative concepts of masculinity.

This contrast also shows that no single queer spoken word performance or queer spoken word performer can challenge all aspects of the heteronormative society they are embedded in, and nor should they have to. In its focus on transgender experience, Smith’s piece becomes part of a canon of queer spoken word poetry whilst other members and performers of the LGBTQ+ community might present very different viewpoints, sexualities, and experiences.

Queer Pasts and Futures

In the trans community, transgender memoirs have played a vital role since their first publication on a wide-scale during the 1930s (Jacques 358). These personal accounts were used to pass on knowledge of transgender living to other trans people and often represented the only source of information on transitioning, thereby offering a vital source of information for the community (Stone, 2013). Aside from detailing the personal and medical experiences of individuals, memoirs and other autobiographical material from the queer community also contribute to a collective queer memory and history otherwise unrecorded (Kim & Reed 6). Spoken word poetry, with its capacity to reach an audience and to be shared and viewed widely with secondary audiences through platforms such as YouTube adds a substantial new chapter to this history. Crucially, by telling stories of individuals, queer spoken word performers contribute the life-stories of an entire community in the form of a queer (online) archive (Arckens 113). Having access to this kind of memory and history allows other queer people to see themselves represented on stage, and create the possibilities of a connection to a queer community which otherwise would have been silenced (See 5).

Spoken word poetry also has the potential to speak a new future into being. In every new phrase it offers the possibility to follow or change rules – grammatical, metaphorical or otherwise. In their paper “Tell the Story, Speak the Truth: Curating a Third Space Through Spoken Word,” Katelyn Jones and Jen Scott Curwood show that poetry offers a “safe space to take risks while manipulating language” (such as grammatical rule-breaking; 284) as well as a “counter narrative that respects young people’s identities and encourages push back against oppressive paradigms” (285). Thus spoken word performances have the potential to reach back into the past, to add to a growing and re-spoken history of the queer community in the present, as well as into the future by suggesting possible ways of moving forward.

Ethan Smith’s performance speaks to both his past as well as his future on an individual and personal level. The present Ethan, as highlighted by his physical appearance, marks how far he has come in this process of transition. Performing the poem, he recounts and writes to an Emily of the past, mourning the future she will not experience, such as “hearing her name called at college graduation” (01:26). However, given the context of his speech at a College Union Poetry Slam 2014, it becomes clear that Ethan is consciously creating that future for himself as a transgender man and as result, his performance signals how queer bodies and queer sexualities challenge normative ways of living.

Smith’s poem “A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be” constitutes only one example of a wide range of queer poetry performances. Projects such as “Poetry Off the Page” and Mitchel Dipzinski’s “A Spoken-Word Poet’s Gestural Guide To Creating A Queer World” are key to establishing pivotal developments within the much needed conversation about queer spoken word poetry in an academic setting.

***

FRANZISKA KLEIN (she/her) is an independent researcher currently based in Vienna. She graduated from Maastricht University (NL) with an M.Sc. in Cultures of Arts, Science, and Technology, focusing on queer spaces and places and queer (historical) urban architecture. Part of her Masters was spent as a research assistant in the Poetry Off the Project, where, between Covid lockdowns and Christmas markets, she fell in love with the city of Vienna.

***

To cite this blog post: Klein, Franziska. “Queer Theory on the Spoken Word Stage.” Poetry Off the Page, 08 October 2024, https://poetryoffthepage.net/queer-theory-on-the-spoken-word-stage/.

***

Works Cited

Ailes, Katie. “Speak your Truth: Authenticity in Spoken Word Poetry.” Spoken Word in the UK, edited by Lucy English and Jack McGowan, Routledge, 2021, pp. 142-53.

Arckens, Elien. “‘In This Told-Backward Biography’: Marianne Moore Against Survival in Her Queer Archival Poetry.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1/2, 2016, pp. 111-27.

Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Duke University Press, 2012.

Dipzinski, Mitchel. Abstract. “A spoken-word poet’s gestural guide to creating a queer world.” Forthcoming.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Duke University Press, 2004.

Jacques, Juliet. “Forms of Resistance: Uses of Memoir, Theory, and Fiction in Trans Life Writing.” Life Writing, vol. 14, no. 3, 2017, pp. 357-70.

Jones, Katelyn, and Jen Scott Curwood. “Tell the Story, Speak the Truth: Creating a Third Space Through Spoken Word Poetry.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, vol. 64, no. 3, 2020, pp. 281–89.

Kim, Jongwoo Jeremy and Christopher Reed, editors. Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry. Routledge, 2017.

Novak, Julia. Live Poetry: An Integrated Approach to Poetry in Performance. Brill, 2011.

Puotinen, Sara. “Queer Hope: Is It Possible When We Have No Future?” Trouble, 15 July 2009, https://trouble.sarapuotinen.com/archives/1620. Accessed 28 November 2024.

See, Sam. Queer Natures, Queer Mythologies. Fordham University Press, 2020.

Smith, Ethan. ‘A Letter to the Girl I Used to Be.’ YouTube, uploaded by Button Poetry, 17 May 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lkn06Y8prDU.

Stone, Sandy. “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto.” Camera Obscura, vol. 10, no. 2, 1992, pp. 150-176.

Strudwick, Patrick. “This Trans Guy Wrote A Letter To The Little Girl He Once Was To Say Sorry.” Buzzfeed.News, 11 Jun 2015, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/patrickstrudwick/from-ethan-to-emily.

***

This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.